Indigenous community in Peru suffers after oil spill

- Published

An oil spill has contaminated the river system in this part of the Peruvian jungle

Oil and water do not mix, anyone can tell you that.

It is a basic rule of science, which certainly holds true in the jungles of northern Peru, at the headwaters of the world's greatest river system.

Not for the first time in recent years, locals have been dealing with the aftermath of a huge oil spill after a trans-Amazonian pipeline fractured, emptying some 3,000 barrels of thick black crude into the jungle river system.

For the last month, workers from Peru's state-controlled petrol company have been mopping up and scooping up much of the oil that stuck to the ravines and vegetation in the smaller rivers.

'Inevitable accident'

No one really knows how much was swept down the River Chiriaco and then into the River Maranon, one of the biggest Amazon tributaries in Peru.

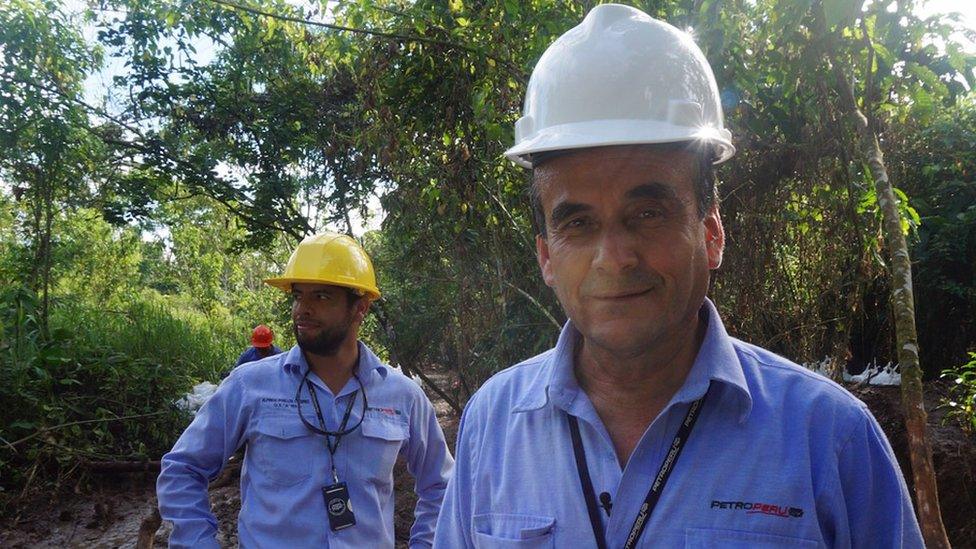

Victor Palomino says accidents are inevitable

Nonetheless, officials from PetroPeru were keen to tell us how well the clean up was going.

The man in charge of the operation is Victor Palomino. He is showing us how thousands of sacks loaded with contaminated earth are being collected and removed for disposal.

Authorities say they are trying to repair the damage to the region

Mr Palomino denies it was a lack of maintenance that caused the 40-year-old pipeline to break, but he admits its unlikely to be the last such incident.

"Yes, of course there will be accidents, that's inevitable," the site chief tells me as we survey the damaged steel pipeline.

"But our biggest concern here is to restore the environment to how it was before and to minimise the risk to local communities," he adds.

This is the second major spill this year in the northern part of Peru's jungle region, not far from the border with Ecuador.

Risky clean-up

But, on top of the environmental impact, we came across something equally disturbing: evidence that children from poor, indigenous communities have been involved in the clean-up.

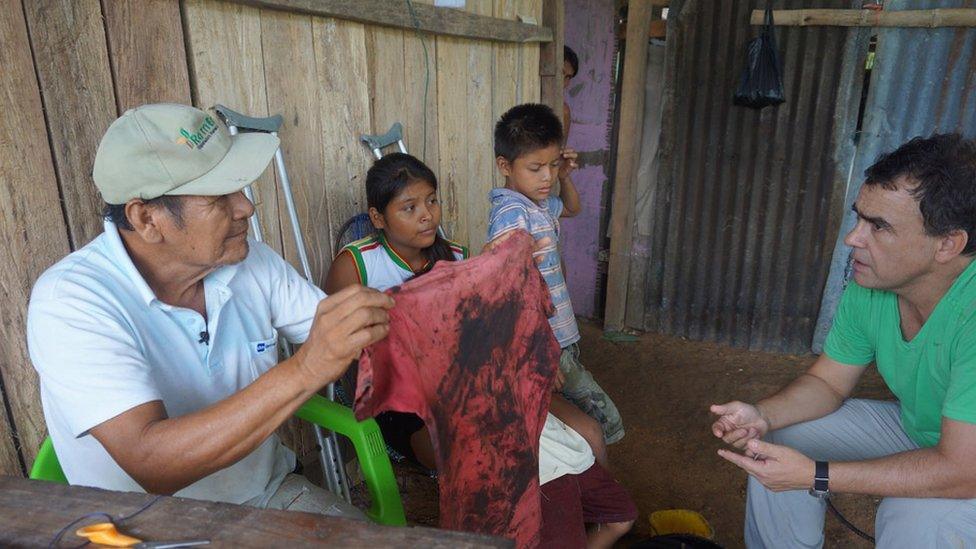

Naith (second from right) and her two brothers say they used their hands to clean up the oil

"With just our bare hands, like this," 14-year-old Naith says and shows me how she and her two younger brothers scooped oil with their bare hands into buckets.

She says that they were paid about a dollar for each one by company officials.

Their father, Jaime, says he stopped them once he found out that they and most other children from the village had been gathering oil for the best part of a day.

"They fell ill with fever and diarrhoea after being sent to the river," says the father of four. His middle son, seven-year-old Osman, is still in hospital.

Jaime shows me the boy's oil-stained clothes - not for him the protective white suits worn by the company employees.

Jaime holds up his son's oil-stained T-shirt

Employees use protective white suits during the clean-up operation

In a statement PetroPeru said it explicitly prohibited the employment of children at the operations centre where it did hire local workers to help in the cleanup.

But the company said it would look into the allegations.

Long-lasting effects

Back out on the river, I watched a small army of workers hard at work removing oil-stained vegetation and debris.

The contaminated soil is shovelled into plastic sacks

The company insists that no expense and no amount of human effort will be spared to clean up this oil spill within a month.

But the effects will last much longer.

There is a state of emergency that means locals cannot use the water or fish in it for four months.

This is a waterway on which their very lives depend.

In the indigenous village of Nazareth, where many locals still live in traditional huts and eke out a subsistence living, one woman shows me her ruined, oil-stained fishing nets.

'Nothing but trouble'

"It's a disaster for our community," Elemina tells me in her native Achuar language.

Removing the contaminated soil is an arduous task

With part of their land now contaminated, locals say oil has brought nothing but trouble to the region.

Environmental campaigners who work with Peru's indigenous communities say the combined effect of impunity for the oil companies and a lack of investment in decades-old infrastructure means that the underlying issues are rarely resolved.

The falling price for oil on global markets means that there is not much new oil exploration going on in the Amazon jungle these days, something that many people welcome.

The downside is that the smaller oil companies who still operate here do not have the resources or will to update and maintain their existing networks.

The Maranon and the mighty Amazon it feeds are big enough to cope with a spill of the size we saw in northern Peru but less certain is the future of the small communities which live alongside the riverbanks.

- Published23 February 2016