INTERVIEWER:Can you remember the first time you heard about what had happened to Ivor as a little boy?

JUDY:Mum told me when I was ten years old, I just remember going into a corner of the room and just sobbing my heart out and from that moment on there was that feeling inside of me that I had to and needed to protect my dad. I did not feel I was able to go to him when I was upset because I didn’t want to and I’ve accepted that I won’t be able to release my demons because I can’t until he has. That’s what I’m hoping I’ll get from today.

Oh my god, the size of it. Oh my god.

TOUR GUIDE:This is a vast complex in which hundreds of thousands of people lived, briefly. Train load after train load of people coming in, replenishing these huts and the slave labour force, about 80% of the people on the trains being taken off to death.

GROUP SINGING

JUDY:Seven hundred people in one, what?!

IVOR PERL:Yeah, seven hundred people in a block and towards the end a thousand.

YOUNG FEMALE:And did you just sleep on this in the hut?

IVOR PERL:Yeah. And in fact this quite sort of modern compared to what I remember ours was, this is brick built ours was wooden built.

JUDY:UNCLEAR

IVOR PERL:What for? What like you?

JUDY:Just you know, you know, for your mum and your dad and your brothers and your sisters.

IVOR PERL:Do you know Judy? All I can tell you is that crying in my heart, it’s there every day.

JUDY:I know it is, I know, I know it’s every day, I know dad, I know. But you’re finally, for the first time today, showing that it’s too painful.

IVOR PERL:Yes.

JUDY:And I can’t imagine what it was like for you. You know, you were a child. I know it’s been stuffed down for so many years…

IVOR PERL:Yeah, exactly.

JUDY:If you open that box you’re scared, you’re so scared because you think that you’ll never be able to close it again.

IVOR PERL:Possibly.

JUDY:I know, I’m sure that’s what it is.

IVOR PERL:So maybe that’s better off to be left alone.

JUDY:I just know for sure that if you were to allow yourself be susceptible to that emotion of sadness, and shed a few tears, it is a healthy emotion and it is part of the grieving process.

IVOR PERL:But as I said the tears don’t have to be in sort of, in water, it can be in other ways as well, hurt in the heart.

JUDY:No, I know but maybe your kids need to see that.

Video summary

Ivor Perl survived Auschwitz-Birkenau as a 12 year old boy. His entire family were deported there. Of his mother, father and eight siblings, only he and his brother Alec survived.

Ivor is returning to Auschwitz with his daughter Judy. It will be the first time that Judy has been to the camp. Growing up, Judy describes the challenge of having a parent who was a survivor and the impact it had on her.

She has asked Ivor to return to Auschwitz in the hope that it can help him, and therefore her, come to terms with the past.

Upon arrival Judy is horrified by Birkenau and what her father went through. She wants him to grieve, for his family and what he endured, so that he can heal and so that she and her siblings can process their own inherited trauma. But Ivor explains that this is too much to ask and that he has his own way of dealing with the pain of the past.

As well as Auschwitz, Ivor survived Allach and Dachau concentration camps.

This clip is from the BBC series, The Last Survivors.

Due to the sensitive nature of the subject matter, we strongly advise teacher viewing before watching with your students.

Teacher Notes

Should sites like Auschwitz remain open to the public? Are tours of these sites a good thing?

Can you sympathise with Judy’s perspective? Are you surprised by the impact that the Holocaust continues to have on the second generation? Discuss what that impact might be.

Do you expect survivors to be emotional?

This short film will be relevant for teaching history at GCSE and above in England, Wales and Northern Ireland and National 4/5 and above in Scotland.

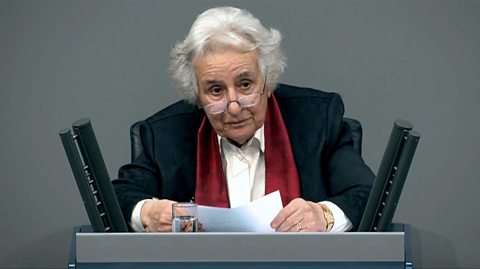

Anita Lasker-Wallfisch addresses German Parliament. video

Anita Lasker-Wallfisch addresses German Parliament to caution against forgetting the past. She contemplates as to what difference speaking out as a survivor can make.

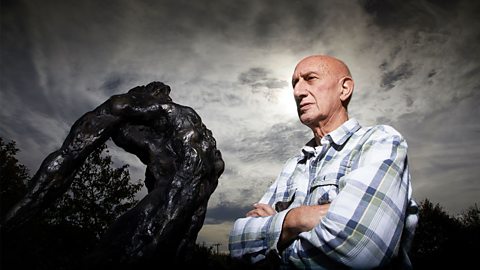

Maurice Blik confronts the impact of his experiences. video

Maurice Blik confronts the impact of his experiences as a child in Bergen-Belsen, recounting the moment his sister died and how sculpture has helped him to process his trauma.

Frank Bright recounts the fate of his former classmates. video

Frank Bright discusses his work researching the fate of his former classmates, using a class photograph taken in 1942 which he calls ‘Red for Dead’.

Manfred Goldberg confronts the death of his brother. video

Manfred Goldberg returns to Germany for the first time since he was a child in 1946 to attend a memorial for his family. In doing so, he finally acknowledges the death of his brother.

Sam Dresner grapples with his memories of the Holocaust. video

Sam Dresner has no photos of his family, who were murdered when he was a boy. He uses art to recreate what they looked like from memory, and to try and process what he saw.