Expecting not to find much more than a pile of big stones, I followed the sign off the motorway into a little car park and there it was, rising from a flat, green landscape covered in little white flowers, with a few donkeys dotted around: Nuraghe Losa. From a distance, it looked like a big sandcastle with its top crumbling away, but as I walked towards it, I began to realise the colossal size of the monument in front of me.

Nuraghi (the plural of nuraghe) are massive conical stone towers that pepper the landscape of the Italian island of Sardinia. Built between 1600 and 1200BCE, these mysterious Bronze Age bastions were constructed by carefully placing huge, roughly worked stones, weighing several tons each, on top of each other in a truncated formation.

Today, more than 7,000 nuraghi are still visible across the Mediterranean's second-largest island. From the flat basin of Sardinia's southern Campidano plain to the rugged hilltops and granite boulder-strewn valleys of its northern Gallura region, these megalithic monuments stand guard over ancient trade routes, river crossings and sacred sites. The instantly recognisable beehive-shaped buildings are not found anywhere else in the world, and so have come to symbolise Sardinia.

Nuraghi are beehive-shaped Bronze Age fortresses that pepper that Sardinian landscape (Credit: Gabriele Maltinti/Alamy)

However, it's still not clear how or why Bronze Age Sardinians of this Nuragic civilisation constructed these imposing towers. Theories about their use range from fortifications and dwellings to food stores, places of worship or even astronomical observatories. The likelihood is that they served several of these purposes during the course of their history, as the towers remained central to Nuragic life for centuries.

In 1953, Sardinia's most famous archaeologist, Giovanni Lilliu, wrote in Italy's Le vie d'Italia magazine, "The nuraghi, for Sardinia are a bit like the pyramids for Egypt and the Colosseum for Rome: testimonies not only of a flourishing and historically active civilisation but also of a spiritual concept that gave its external manifestations a monumental and lasting character."

Lilliu is best known for his excavation of the island's most elaborate Nuragic settlement: the Unesco-inscribed Su Nuraxi, consisting of a fortified central nuraghe surrounded by a honeycomb structure of round, interlocking stone huts spilling down the hillside. In addition to Su Nuraxi, two of Sardinia's most important nuraghi are Nuraghe Arrubiu – a monumental five-lobed bastion whose 30m central tower was one of the tallest structures in Bronze Age Europe – and Losa, which consists of a central keep surrounded by three smaller towers encased by a curtain wall. Today, the structure stands 13m tall, but in its heyday, experts estimate the complex would have been nearly twice that.

Sardinia's best-known Nuragic complex, Su Nuraxi, is a veritable megalithic castle (Credit: Robert and Monika/Getty Images)

Entering Losa through a narrow gap in the lichen-covered stone wall, I found dark passageways, framed by huge, rounded rocks, leading in different directions; and above me, a 3,300-year-old ceiling that resembled an inverted pine cone. To my great surprise and amazement, a spiral staircase hidden in the inner walls led up to the roof of the building. Although worn down to more of a rocky slope in some places, the staircase is still so perfectly functional that I walked up and down several times, imagining all the people who would have trodden those steps before me.

The top offers a perfect vantage point from which the Nuragic people could gaze out over the then-untamed, forested landscape to watch for potential threats. They would have also spotted other nuraghi in the distance, leading historians to believe that the structures weren't just symbols of power and wealth, but also an island-wide communication chain – "a bit like the internet", said Manuela Laconi from the organisation Paleotur, which manages the Nuraghe Losa site.

Since 2002, Laconi has been involved in the Losa's preservation, and she's still captivated by the site and the secrets it holds. "I feel very proud to be working here," she said. "This [type of] monument was very important for the Nuragic people, and it is still so very important for our island. It is our culture, our tradition."

Nuraghe Losa is 3,300 years old and consists of a central keep surrounded by three smaller towers encased by a curtain wall (Credit: Kiki Streitberger)

But who were these highly skilled builders and craftspeople that populated Sardinia at a time when the Egyptian empire was at its height?

The Nuragic people get their name from the civilisation's most recognisable engineering feat. Since they didn't leave any written records behind, what we know about their way of life is an incomplete jigsaw puzzle pieced together through their many monuments, the tools and utensils found in their dwellings and, most importantly, from their small and intricate little bronze sculptures (bronzetti). The British Museum in London has a few in its collection, but the most complete display can be admired in the National Archaeological Museum in Sardinia's capital, Cagliari.

There, you can come face to face with an ancient Sardinian chief wearing a long cloak and a ceremonial dagger strapped to his chest. Female figures dressed in straight tunics and capes with tall, wide-brimmed hats are thought to have been priestesses, while others holding soldiers and babies seem to have taken the role of caretakers. Many figurines carry gifts of food. One has a small goat slung over his shoulders and another seems to offer a plate of Bronze Age doughnuts. "They represent all the different aspects of [Nuragic] society," said Nicola Pinna, from the National Archaeological Museum in Cagliari.

The vast majority of bronzetti, however, are warriors, leading scholars to think the Nuragic people were a war-like society organised into military divisions. Sword- and stick-wielding soldiers and archers are depicted wearing plumed or horned helmets and high metal collars. Many carry round shields, and some are protected by elaborate armour and masks to scare their opponents. "It was a military civilisation… where the various different clans would have fought against each other," said Pinna.

Much of what we know about the Nuragic civilisation is through their small bronzetti statues (Credit: Massimo Piacentino/Alamy)

Bronzetti have been found all over Sardinia – in nuraghi, tombs and temples. But an unusually high number have been retrieved near the 70 or so sacred wells that the Nuragic people also built across the island, leading experts to believe that they were votive offerings given to the gods and goddesses.

As Lilliu pointed out in his numerous publications, Nuragic religious practice was linked to the worship of water.

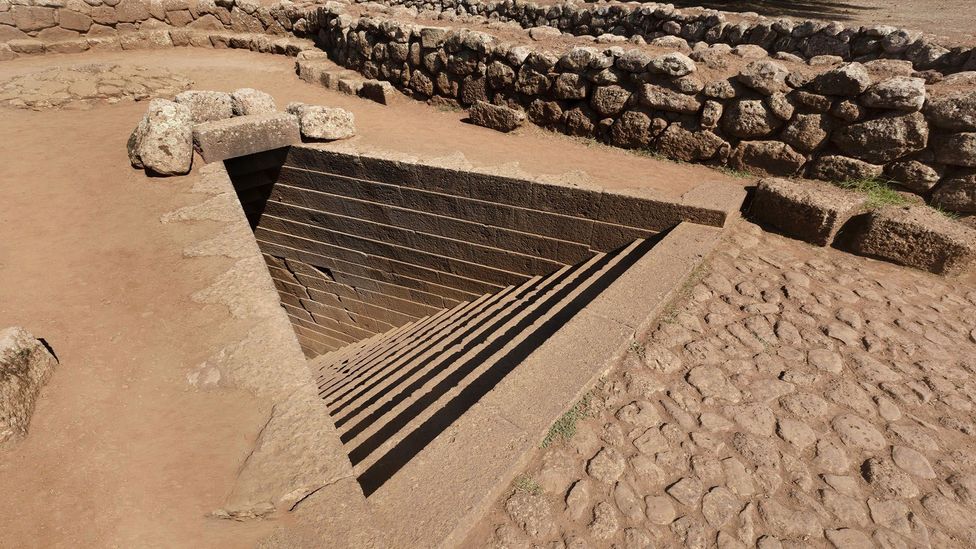

The best-preserved well is the Sanctuary of Santa Cristina, located in the village of Paulilatino, in the central-west part of the island. "Its perfection and size are the most important characteristics," said Sandra Passiu, who has been involved in the maintenance of the site for the last 20 years.

On a plateau surrounded by olive trees, a triangular staircase built from basalt blocks so perfectly hewn it appears to have been made only yesterday leads down to the sacred well inside a domed, underground cavity. The well temple was designed to align perfectly with the equinoxes, and each year in March and September, the sun illuminates the water at the bottom.

The nuraghi builders also constructed sacred wells, like the immaculately carved one at Santa Cristina (Credit: Andrea Raffin/Alamy)

"At the time of the equinoxes, when the sun is perfectly aligned with the temple [there is] a very strong energy, a positivity, a form of well-being," Passiu said. Even more extraordinarily, every 18-and-a-half years, when the moon is at the highest point in the sky, its light shines through a little hole at the centre of the dome above the well to reflect on the water below. The next occurrence is scheduled for June 2024.

In recent years, an increase in archaeological research is revealing more details about this civilisation. Earlier this year, Italy's leading news agency, ANSA, reported that two sandstone statues were unearthed at Sardinia's most famous necropolis, Mont'e Prama.

The 3,000-year-old sculptures (commonly called "giants") stand between 2 and 2.5m tall and are the two newest members of a colossal army of archers, warriors and boxers thought to have guarded the Nuragic burial ground. The exact origin and purpose of these sculptures remains shrouded in mystery, but they have become the faces of Sardinia's Nuragic past since two farmers accidentally discovered the necropolis in 1974.

Archaeologists, historians and politicians are excited by these latest finds and there is hope that more money will be made available for archaeological excavations in the coming years, to shine more light on Sardinia's ancient origins.

Mysterious 3,000-year-old sculptures called "giants" continue to be unearthed in Sardinia (Credit: Kiki Streitberger)

For Sardinians, the thousands of nuraghi and the other traces of their civilisation aren't just reminders of the past, but a ubiquitous part of the present. In many ways, they are the physical manifestation of the Sardinian soul.

"I am not Italian, I am sarda (Sardinian)," said Laconi, a feeling shared by many on the island. "Sardinia is not Italy." Traditions linked to Nuragic practices still live on in the horned masks worn at the carnival celebrations and in the bagpipe-like sound of the launeddas, the triple flute found in the hands of a bronze Nuragic sculpture.

The sun high in the blue sky, I left Nuraghe Losa behind and walked back through the flowering meadow, knowing that there was still an entire village waiting to be unearthed below my feet.

Unearthed is a BBC Travel series that searches the world for newly discovered archaeological wonders that few people have ever seen.

Join more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "The Essential List". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.