This is the only picture of Henry Cavendish, and the reason is that he was very uncomfortable about sitting for portraits, in fact he never did it. So this was done mainly by an artist who glimpsed him over dinner and then sketched it out from memory, and it shows all the essential eccentric features of the man. He's wearing a hat which has been described as something from the previous century. And he always wore the same coat and he liked it so much that every year when it wore, he had a new one exactly the same tailored.

Cavendish's eccentricity was combined with a far more important trait for a scientist: an insatiable sense of curiosity. His main aim in life was to weigh, number and measure as many objects as he possibly could.

And fortunately, like many scientists at the time, he was fabulously wealthy so he was able to indulge his curiosity with hundreds of extraordinary experiments. Like this one, which he first reported in 1766.

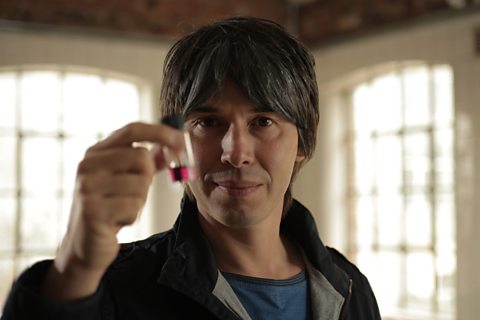

It involves taking a metal, we'll take zinc, and then I'm going to pour concentrated hydrochloric acid onto the zinc.Now I'm going to bubble the gas that's produced into this soap solution, so these bubbles are now going to be filled with this gas, and very quickly and carefully I'm going to light the gas. (explosion) Now, Cavendish called that not um not-, not inappropriately I suppose inflammable air. It's the gas that we now know as hydrogen.

But Cavendish didn't stop there, he doggedly continued his quest to quantify hydrogen until he could describe every aspect of its existence. First, he wanted to see how it would react with other things, like air.

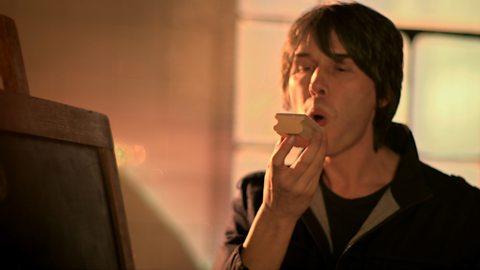

So, I'm going to repeat Cavendish's experiment again but this time with a vessel. What I'm going to do is fill it with hydrogen, so that's full of inflammable air, and I'm going to light the spark.

(explosion)

Now, what you saw there was a chemical reaction, the reaction of hydrogen with air, and if you look closely on the sides of the flask you'll see that it's-, well it's wet. That is water and it's appeared as a result of the chemical reaction.

In many respects Cavendish embodies what science and what being a scientist is all about. His curiosity about the world drove him to design experiments in an effort to gain new insights into the way the world works.

Now Cavendish didn't really have any idea what happened in these chemical reactions, indeed his whole theoretical framework was nonsense to modern eyes, it was based on alchemy. Because he was a great experimental scientist his measurements were correct, so he managed to measure that water is made of two parts of hydrogen to one part of oxygen, H2O, even though he didn't believe that water was made of anything at all. So, that ability to get your theoretical picture, your ideas about the way that nature works completely wrong and yet make honest and precise measurements that stand the test of time and are correct, is the mark of a great experimental scientist.

Cavendish has rightly gone down in history as one of this country's greatest scientists, but perhaps he should be remembered more for his association with another aspect of science, because he was instrumental in establishing this place at 21 Albemarle Street, London. The Royal Institution. Where the vision was that the public could hear of the great discoveries of science.

The Royal Institution became a platform for a new breed, the science personality. From Humphry Davy, the showman who famously danced with joy at his scientific discoveries, to Michael Faraday, who began the tradition of giving the now famous Christmas lectures, and the theatre is still used by scientists to engage with the public to this day.

If now I remove the filter (explosion), something happens.

(explosion & applause)

Audience:

Yes! (applause)

Brian:

Britain was amongst the first countries to understand that the pursuit of science is a vital part of nationhood. So I would like you to grab some of that hydrogen in the soap bubbles…

(explosion)

James:

Aouch!

Brian:

Are you alright?

– and it’s realised that public engagement ensures sciences bloodline.

Video summary

Brian Cox describes Henry Cavendish's shy and eccentric personality, his wealth and his intense scientific curiosity.

He repeats Cavendish’s experiments to produce and investigate hydrogen and its reaction with oxygen to produce water, deducing the formula of water as H2O by recording experiments accurately, despite not having the theoretical grounding to explain what he had discovered.

Cox then goes on to describe the contribution that Cavendish made to the foundation of the Royal Institution, where members of the public could listen to lectures given by scientists.

This short film is from the BBC series, Science Britannica.

Teacher Notes

Encourage students to discuss the personality traits that one might need to be a good scientist.

This short film could be used to demonstrate that science is not just about discovering new knowledge, but also about sharing that knowledge with other scientists and the public.

This short film will be relevant for teaching chemistry at KS3 and KS4/GCSE and National 4/5 and Higher in Scotland.

This topic appears in OCR, Edexcel, AQA, WJEC KS4/GCSE in England and Wales, CCEA GCSE in Northern Ireland and SQA.

Who was Humphry Davy? video

Brian Cox follows in the footsteps of 19th Century chemist Humphry Davy, recreating one of his explosive experiments that he used to impress the crowds at the Royal Institution.

William Perkin and making scientific discoveries by chance. video

Brian Cox uses William Perkin's discovery of mauveine to explain how scientific discoveries are sometimes made by chance.

John Hunter and public engagement in science. video

Brian Cox describes how John Hunter pushed the boundaries of medicine using corpses obtained from grave-robbing and how he set up a museum to open minds about medical research.

Sir Isaac Newton and the scientific method. video

Brian Cox outlines the historical context of the era in which Newton began to be interested in the nature of the visible spectrum obtained using a prism.

John Tyndall and blue skies research. video

Brian Cox describes the work of John Tyndall and his attempts to explain what makes the sky blue and the sunset red.

Targeted research. video

Brian Cox learns about targeted research in the modern pharmaceutical industry and how by focusing only on positive results, it fails to report negative results.

Global warming resistant GM crops. video

Brian Cox outlines the history of the discovery of DNA and how this has led to a controversy over the use of genetic modification in agriculture.